Publisher: Duckworth Overlook

Note this review will be published in the Journal of Macromarketing.

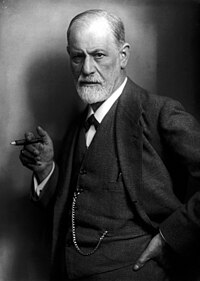

The popularity and import of psychoanalysis has waxed and waned over the decades since its inception via the works of Sigmund Freud. Originally conceived as a method for clinical practice, its theoretical richness and inherent fascinating nature ensured psychoanalysis’s broad spread across theory, humanities, popular culture and, of course, marketing practice. Influential figures like Edward Bernays (Freud’s nephew) and Ernest Dichter imported and applied psychoanalytic theory into evolving practices of marketing research and public relations, giving rise to concerns about the potential of commerce to appeal to our subconscious: practices notionally exposed via the publication of Vance Packard’s 1957 bestseller Hidden Persuaders. More broadly, Adam Curtis’s recent excellent BBC documentary series, The Century of the Self, suggests that psychoanalytic applications have extended the logic of the consumer mindset and mediates contemporary life and political economic macro culture. Despite detractors psychoanalysis has been hugely influential.

The popularity and import of psychoanalysis has waxed and waned over the decades since its inception via the works of Sigmund Freud. Originally conceived as a method for clinical practice, its theoretical richness and inherent fascinating nature ensured psychoanalysis’s broad spread across theory, humanities, popular culture and, of course, marketing practice. Influential figures like Edward Bernays (Freud’s nephew) and Ernest Dichter imported and applied psychoanalytic theory into evolving practices of marketing research and public relations, giving rise to concerns about the potential of commerce to appeal to our subconscious: practices notionally exposed via the publication of Vance Packard’s 1957 bestseller Hidden Persuaders. More broadly, Adam Curtis’s recent excellent BBC documentary series, The Century of the Self, suggests that psychoanalytic applications have extended the logic of the consumer mindset and mediates contemporary life and political economic macro culture. Despite detractors psychoanalysis has been hugely influential.

Link to part one of Curtis's Century of the Self

Makari’s Revolution in Mind: The Creation of Psychoanalysis explores the genesis of Freud’s theories and their dissemination across scholarship and clinical practice. The book begins with the arrival of Freud in Paris in 1885 as he embedded himself in the thriving hospital research tradition of great institutions like the Salpêtrière. Freud studied major medical researchers like Jean-Martin Charcot and Auguste Comte, their research into hysteria and innovations relating to hypnosis. Makari reveals Freud to be a master of synthesis, incorporating ideas from various fields into his unfolding intellectual project of the inner world. Freud mined fields of sexology, psychopathology, biophysics and philosophy, borrowing and synthesising ideas and is presented as master of dialectical interdisciplinary engagement. By 1899, Freud had arguably his first serious articulation of psychoanalytic ideas with the Interpretation of Dreams, in which we see the development of what would become theories of the subconscious and Oedipal Complex. The limits of Freud’s ideas were already manifest with Comte critiquing that any psychology so subjective in origin could never transcend personal prejudice and achieve scientific consensus. This critique not only prophesized the hostility from the wider world of clinical practice, but also poses the question of whose psychology was central to analysis: Freud’s, his detractors, a full hysteric?

As a group of Freudians started to gather, discuss and propagate ideas, the intensity of this latter enigma of whose psychology came to dog social interactions between the emerging advocates. Makari fascinatingly explores the formation of a Wednesday Psychological Society who would convene in Freud’s Vienna home and, it seems, feud under Freud’s watchful eye – sometimes distant and allowing diversity to emerge, but other times polemical and set to the bitter task of removing heretics. The emergence of the Zürich School, which included such major scholars as Paul Bleuler, director of the prestigious Burghölzli centre at the cutting edge of clinical therapy and brain research, and also Carl Jung whose work eventually rivalled Freud’s, were to lend empirical, international and institutional credibility to Freud’s ideas. In 1908 a congress was held in Salzburg which eventually lead to the creation of the International Psychoanalytic Association. Almost immediately the Association became defined by its tangled web of envy, jealousy, paranoia and ambition.

Sigmund Freud

Makari reveals a group sometimes best understood in terms of its own dysfunctions: for example it is suggested that Fritz Wittels’ polemics against women doctors revealed more about his own seething psychosexual dilemmas. Alfred Adler’s insistence on behaviour as a type of compensation for weakness was understood by some colleagues as an act of self-relating whilst Freud was suspected of being obsessed with sex and had apparently became locked into father-son rivalry with Jung. Bitter confrontations ensued with Adler and Wittels forced out of the Wednesday Psychology Society whilst Jung eventually resigned his presidency of the International Psychoanalytic Association amidst acrimony. Meanwhile psychoanalytic practice was regularly undermined by controversial counter-transference sexual relationships with patients and concerns about wild analysts.

For a field with so many Jewish exponents the tragic unfolding of events across Europe lends a dark backdrop to Makari’s account. The book details the sad scramble of psychoanalysts to safety in England and America as the impressive European network that had formed by the 1930s was all but wiped out. Psychoanalysis lived on during the Third Reich with Matthias Göring, cousin of Herman, taking control of the German institutions and identifying Mein Kampf as a text worthy of scientific study. By the end of the war at least fifteen psychoanalysts had been murdered by the Nazis and only two of the original Salzburg congress had survived. Makari concludes with accounts of nomad clashes: the London group suddenly became swamped by Viennese counter-parts and conflict immediately ensued between Melanie Klein and Anna Freud, whilst in the USA, where the psychoanalytic community had not yet established any particular school of thought, the Europeans adopted the manner of “dispossessed royalty” with depressingly predictable results.

Overall Makari’s Revolution in Mind presents an excellent and high quality overview of the emergence of psychoanalysis. Makari’s summarizing of complex positions is enormously helpful for those of us seeking to trawl through the confusion of conflicting schools. The text provides brilliant analysis of the social process of paradigm formation against background tensions spread across temporal, sectarian and geographic terrains. Makari is strongest demonstrating Freud’s dialectical process of theoretical development and locating Freud’s early works amongst the various intellectual traditions that he was borrowing from but a question that perhaps remains unanswered is how Freud’s ideas spoke to the cultural transformations of modernity that defined early twentieth century Europe. Just why were Freud’s ideas so charismatic and how are we to understand the wider diffusion of psychoanalysis into popular culture and imagination? Whilst Makari leaves us wondering, these very questions form the basis of Zaretsky’s recent Secrets of the Soul: a Social and Cultural History of Psychoanalysis providing a neat complementarity between the two important texts. Revolution in Mind is to be recommended for anybody interested in Freudian theory, paradigm development, European history and the development of theory fundamental for understanding identities, subjectivities, consumption and culture in modernity.