|

| Chet Baker whose notorious self-destruction seems to have inspired audiences |

The first question we must ask ourselves in pondering the relationship between art v commerce is why this should matter to us at all. At worst, the preoccupation of art v commerce may speak to a middle class anxiety, an anxiety borne of a flat ontology which seeks its antidote through cultural consumption. Within this grid of analysis, cultural production is reviewed in terms of whether or not it embodies truth, authenticity and subjectivity. Herein musicians are carriers of a class’s desire for authenticity and therefore must commit their careers to being a performance of such values in order to meet the demands of an audience who typically live to no such personal standards themselves. Taking the lifestyle to its full extreme and publicly self-destructing– as per the case of Chet Baker I previously developed with Morris Holbrook here – apparently satisfies this public demand and so exposes the deep problem of this desire, which places huge expectations on the shoulders of musicians in terms of their scope of professional conduct and their lifestyles.

|

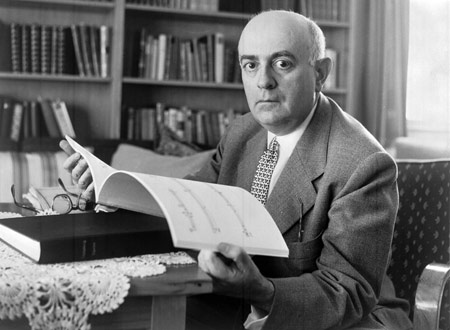

| Theodor Adorno whose mode of analysis is described as a foundational trauma for music studies |

From another perspective, we might query as to whether the academic fixation, especially as it typically arises within music studies, attempts to resolve a post-Adorno impasse. By centring analyses onto how the musical commodity - as any music becomes rendered as a commodity in a cultural industry - reproduces modes of industrial production that reify any meaningful cultural content in capital’s image, Adorno presents an authoritative mode of critique that becomes very difficult to work around. As Krimms has argued, Adorno’s intervention has become a “foundational trauma” for music studies because it tends to exhaust most forms of music and leave music lovers with very little scope for optimism or radical intent. This problem is all the more so because in Adorno’s preference for deeply esoteric music – most notably Schoenberg –, a sheer difficulty arises in nominating any music that can escape Adorno’s critique and hence Adorno’s argument has had the effect of strangling most forms of analysis (I wish to make clear that I am not repeating the stale argument of Adorno as an elitist). My argument, then, is that successive authors (including my earlier work) have perhaps sought to conduct analysis post-Adorno by displacing Adorno’s analytic question towards ones of authenticity within the arts v commerce question. If this argument is true, then a large portion of analysis that perseveres with this analytic lens does so as an act of displacement, a way of avoiding engaging with the extremely difficult questions set in motion by Adorno. Therefore there is a case to be made to say that the art v commerce question was always ever a fake question, one that intersects with petit-bourgeois anxieties and adds nothing to the politics of engagement. We can contrast this dead end with the more politically determined work that we see within other fields, for example as detailed in the recent ReNew Marxist Art History as edited by Carter, Haran & Schwartz.

|

| Lauren Berlant, author of Cruel Optimism |

A further issue may arise if we consider the problem of art v commerce as one that inhibits artistic possibility. There is something tragic, it must be conceded, in watching a musician intent on a career in the avant-garde playing instead the Girl from Ipanema in a provincial hotel lobby as a form of background music for a transitory non-audience. Within this spectacle, we might see what Lauren Berlant refers to as the ‘cruel optimism’ of capitalism which typically renders the object of desire as the object that is actually the obstacle for personal flourishing. Hence the ambition to be an avant-garde musician will probably condemn the musician to a career of precarity and obscurity whereupon he/she will be dependent on menial forms of labour to temporarily make ends meet. Accordingly, we may conceive of art v commerce as indicative of capital’s ability to limit our creativity and general propensity to flourish. From this perspective, we should identify the precarious forms of working inscribed within capitalism as the problem and consider the issue to be one of infrastructure. Further, we should recognise in the tragic performance of the Girl from Ipanema how we all remain attached to unachievable fantasies of the good life – be they upward mobility, job security, political and social equality and durable intimacy – which have all been undermined by contemporary capitalism (see the arguments pursued in Cruel Optimism by Lauren Berlant). If jazz appreciation is the art of hearing the notes that are not being played, we might take this way of listening much farther and also query the gap between what we are listening to and what the musician might prefer to play.

|

| Crowds gather for the Federal Theatre Project's perofrmance of Macbeth in 1936 |

Arguably, one of the golden periods of flourishing in US cultural history took place during the New Deal for the arts. The Federal Theatre Project cut across class and racial divisions and pushed the boundaries of what could be performed beyond the corporate filter. Some of the most radical shows of the century emerged including the so-called Voodoo Macbeth and the ill-fated Cradle Will Rock. The biopic movie, Cradle Will Rock, that charts the rise and fall of the Federal Theatre Project, concludes with an evocative scene (see https://youtu.be/rqPE0YYgwjI?t=7177) wherein the performers who had benefitted from the New Deal carry a now useless marionette through the Broadway theatre district of 1937, walking away from an epoch characterised by Orson Welles, Marc Blitzstein and Hallie Flanagan. Their procession is juxtaposed with the bittersweet celebration that followed the conclusion of the only performance of Cradle Will Rock -an enormously compromised affair, stripped down to its bare minimum in the face of a determined opposition to the show being performed at all - and the smashing to pieces of Diego Rivera’s mural inside the Rockefeller building. The cortege concludes in contemporary Times Square whereupon we are forced to behold the grotesque, garish spectacle of the now overly commercialised cultural wasteland. Viewers are beckoned to contemplate how the contemporary entertainment circuit is built upon the ruins of a once vibrant state subsidised avant-garde that was destroyed by a now hegemonic deeply reactionary counter politics. In this scene, the politics of art versus commerce are made uncomfortably explicit and, by identifying the political fault lines and observing how we all suffer a lack of infrastructural support, we see why art v commerce matters.

A final example of how we might approach the question is raised by the possibility of a mode of analysis that explores how art might specifically pressurise capitalism. As distinct from analysing the content of the music itself, searching for signs of reification a la Adorno, instead a study might present a historical analysis of how the music specifically comes to make spatio-temporal contestations against capitalism and to assess particular moments of pressurising power. In this regard the music ought to be explored in terms of how it caters for new forms of gathering, shared experiences, and politicised subjectivities and to understand the infrastructural conditions that lead to such possibilities. Such analysis should of course probe the axiomatic assumptions that underpin the analysis itself, persistently subjecting itself to reflexive doubt. To nominate a recent text that combines Marxist art history with music studies, Owen Hatherley’s Uncommon (2011) reviews the career of English band Pulp (see an abridged version here). Hatherley reviews Pulp’s output, detailing how the music challenged class stereotypes and registered anger and resentment against the class warfare endemic to the late twentieth-century Britain. Hatherley locates the band’s career within a particular infrastructure centred around art school education, arts council grants, council housing, and social welfare payments. Hatherley’s reading of Pulp of the 1990s also allows for us to critique contemporary British politics and also to notice something often overlooked in music studies: working-class musicians are rapidly disappearing from public view.

No comments:

Post a Comment